Everybody has a story.

Each of us has a story that’s uniquely ours, though it may have been forgotten in the hubbub of daily life: the blare of alarm clocks, getting everyone up and out of the house on time, job demands and annoyances, financial worries, unexpected emergencies.

Sometimes it’s hard to recall that special moment or event. When we hear others tell their tales, we may tend to think our lives are tediously predictable and tame—though predictable and tame can be blessings, and we should count them.

I’m one of those people who forgot. My life has been blessed with what I used to think was normal: happy, healthy childhood; happy, loving family; food and shelter. Very Donna Reed, Leave It to Beaver, and Father Knows Best all rolled into one (minus the hats and gloves for PTA meetings and errands). I thought it was that way for everyone. Then I learned differently. The TV norm, mirrored in my own family life, was not the norm at all. It was a sad awakening.

In all the normalcy of my life, I completely forgot two most unusual events, one major and one not so much. But both are events that make my story a little different from the stories of other folks in my orbit.

The first was the decision the Gnome and I made to move to a land of strangers hundreds of miles from the known, leaving our jobs and other security blankets behind, to hand-build our own home in the country, just the two of us. It was a remarkable risk and a singularly unlikely step for us to take. Its very significance may be what pushed it to the back of my mind as part of my unique story.

It was a major life decision, but it quickly became the everyday. What brought us here and has guided our decisions and processes is part of our daily life, so it’s become our normal, something it never occurs to me to bring up by way of introducing who I am. Yet it’s the very definition of who I am. I tell that story here. (It’s a nine-part series interspersed with blogs on other subjects—just click your way through for the whole story.)

A totally different aspect of my personal story was a single event, one based purely on luck. At the time, the Gnome owned and managed a small travel and map store. He sold lots of outdoor products and thus was invited to attend the annual Outdoor Retailers’ Market, then held in Salt Lake City. The organizers planned a drawing for free tickets, lodging, and airfare for two to the market. Although he’d never attended one of these markets and assumed he never would, he figured he might as well enter the drawing. He was astonished when he got the call that he’d won. And just like that, we were off to Salt Lake.

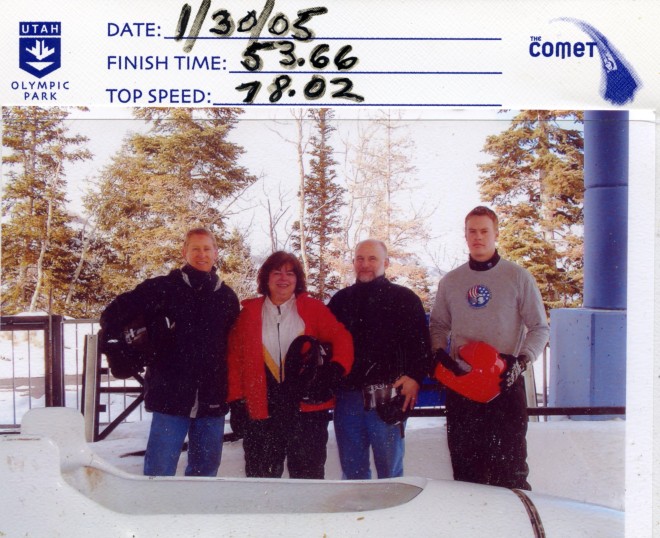

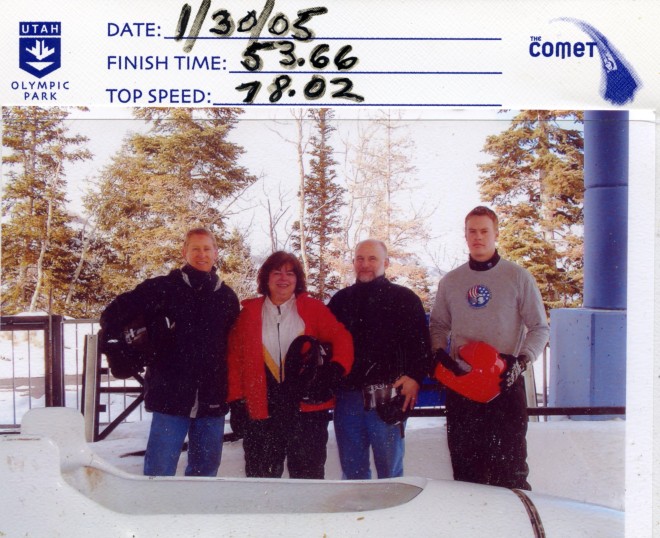

The prize package included a few other perks, one of which was a bobsled ride on the Park City Olympic run from Utah’s hosting of the Winter Olympics of a few years previously. I’m not much of an outdoors person and had never taken up any winter outdoor activities the other side of rushing downhill in a plastic sled. But I was ecstatic about that once-in-a-lifetime chance to do something pretty amazing.

The Olympic Park officials are no fools. They provided an experienced driver for us novices. We were given a brief preliminary lesson, and, of course, we had to sign a waiver which reminded us we were doing something pretty darned risky. The waivers dire language did nothing to dissuade us.

We didn’t set any records, but within mere seconds we were hurtling down that run at seventy-eight miles an hour, our brains bashing against our skulls, our skulls smacking violently against our helmets, and our helmets cracking against helmets in front of and behind us which, in turn, snapped our necks to and fro in full whip-lash fashion.

Meanwhile, we barreled down the earth-shatteringly bumpy run at what felt like faster-than-light speed. Imagine, if you will, plunging down a steep mountainside full of jagged boulders—it might be almost as treacherous as our bobsled ride. In less than fifty-four seconds (a lifetime, let me add) it was all over. I never want to move that fast again!

You can tell this is the “before” picture because we’re all smiling. They wouldn’t have dared to take an “after” photo!

By the time we crawled our stomach-churning way out of the sled and onto the welcomingly motionless ground, our brains were so scrambled we suspected permanent damage. To this day, I feel justified blaming any poor decision-making or forgetfulness on that bobsled ride.

As much as we anticipated our Olympic moment, the reality was utterly terrifying. I thought it would never end and for the only time in my life, I wished for an immediate death.

Knowing what I know now, I’d probably opt out of that once-in-a-lifetime “opportunity.” But if I’d chosen not to do it, I know I’d still have regrets for passing it up. What we regret is usually what we didn’t do.

But it will never, ever happen again!

How about you? Big or little, on-going or momentary, funny or serious, good or bad, what would you include in your story?