My Year in the Yellow House: Childhood Vignettes (part of my Blowing on Embers series)

I was five the year we lived in the yellow house. My brother was two. Our little two-bedroom home in Florence, South Carolina, near Cole’s Crossroads, was part of a modest and sparse subdivision, if you could even call it that. There were no sidewalks, and grass grew erratically in the sandy yards. Roads in the development were nothing more than not-too-packed sand.

My brother’s favorite place to play was on the sandy road in our neighborhood.

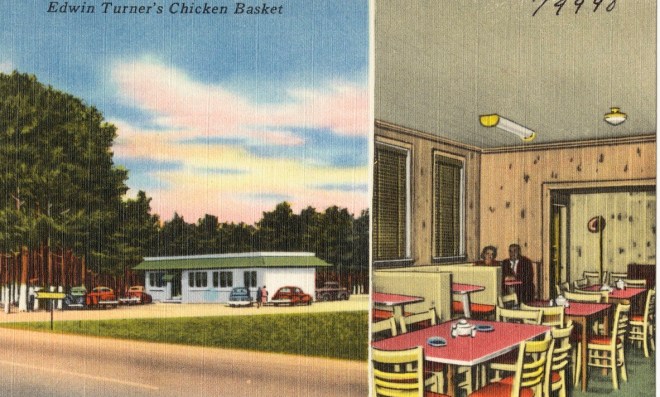

Our house sat on a corner of the neighborhood’s main road. Follow it for a block or so and you’d be on old Hwy 301/52. Directly across the highway was Edwin Turner’s Chicken Basket, a popular family restaurant and the favorite spot for our very occasional meals away from home. As the name suggests, the restaurant’s main fare was fried chicken, along with french fries and hush puppies,* served in brightly colored, paper-lined plastic baskets—the kind you now see in a few casual dining establishments, but a true novelty then. We usually chose a booth in the knotty pine dining room, and Edwin Turner himself would stop by to ensure we were enjoying our meal.

Out front was the sign proclaiming the name of the place. As I recall, atop the sign sat a large rotating replica of one of those famed plastic baskets. My brother could never keep the words for Edwin Turner’s Chicken Basket straight. He always called it Chicken Edwin’s Turning Basket. When you think about it, his literal rendering made perfectly good sense—as children’s name mash-ups often do.

We loved the Chicken Basket—for its tasty food, its novelty, the attention of its owner, its prominent role in our lives. In addition to special dinners out, Edwin Turner’s was a true landmark in the community. For us, it was the easiest way to direct friends and out-of-town family to our house.

But the restaurant is only one of many memories I have of that year. They are a mixture of good and bad. It was while we lived in the yellow house that my first real childhood friendships developed. It was also where I experienced my first significant encounters with sickness, trauma, and grief.

My childhood preceded the era of many vaccines in use today, and I was in bed with a severe case of mumps for what seemed like forever. The lumps on either side of my neck felt humongous, and the pain of swallowing was so intense that I demanded something to spit into so I wouldn’t have to swallow. Of course, it didn’t work, but I gave it my best, spitting several times a minute all day every day into the blue and white speckled enamel pan Mother placed next to my bed. To this day, I have an aversion to enamel cookware.

Glory (not her real name), with her white-blonde hair, lived across the street from us. She had a tumor on her lower back, just above her buttocks. Her parents’ religious beliefs prevented them from seeking medical attention for Glory, but the tumor must have been extraordinarily painful because Glory, who only wore dresses, didn’t wear underpants—the pressure would have hurt too much.

Neither Glory’s illness nor her family’s deeply held religious beliefs kept her from being a bully, though. One day when we were playing in my bedroom, Glory locked me in the toy cabinet and refused to let me out until I gave her permission to tear my doll’s hair off her head. I was terrified in the pitch black cabinet, and I was devastated at the thought of what was happening to my precious doll. Mother was in the kitchen just a room away, but the cabinet doors and the wall between us must have muffled my piteous crying.

My very best friend, Teddy, lived on the third corner of our intersection. We played together much more often than I played with was tortured by Glory. One of Teddy’s and my favorite places to play was in the abandoned excavated lot on the fourth corner of our intersection. We loved it down there where our imaginations could run wild.

Then Teddy had a birthday—his sixth. When I got the invitation to his party, I was inconsolable. Six was when children started school; it stood to reason that Teddy would start first grade without me. It took both my parents and his ages to convince me that I, too, would be six before school started. Teddy and I would still enter school together, they assured me. (It turned out to be a moot point, anyway, since our family moved to another state before the school year began.)

Celebrating Teddy’s sixth birthday—no longer afraid he’d start school without me

Another playmate—another Carol—lived on the far corner of our street. She rounded out our little circle of playmates. Carol and I shared more than a name. We were exactly the same age, born the same day. We were also both dark-eyed, dark-haired, olive-skinned little girls. We could have passed for twins. I can still see the heavy bangs that framed her round face.

One day Carol was hit by a car. She was hospitalized for a few days before dying from her injuries. We didn’t have a telephone and Mother didn’t drive, so she had no way of delivering the terrible news to Daddy. When he came home from work that day, he found Mother crying in the kitchen. She blurted through her tears, “Carol died today.” It was Daddy’s shattered look that made her realize he thought she meant me.

You might expect Carol’s death to be my big trauma from those days. But the truth is, I remembered nothing about it until my mother recently reminded me of it. I was either too young to understand what was going on or I was, in fact, so traumatized that my mind blocked the whole experience.

From time to time a few other random memories of our year across from “Chicken Edwin’s Turning Basket” flutter through my mind. Late one night, we were awakened by sirens and flashing lights. The whole neighborhood stood and watched as a nearby house burned to the ground, its occupants standing alongside us in their pajamas, watching helplessly as their house went up in flames.

The image of them, pajamas now the only clothing they owned, was indelibly seared into my brain. Ever since that night I’ve thought losing my home and its treasured contents to fire would be one of life’s worst tragedies. All these years later, when coming home from an out-of-town trip, I reach the bend our house is just around only to realize I’ve been holding my breath for the last little bit, waiting to be sure our home is still there, still intact.

My brother and I shared a bedroom in the yellow house. Our parents were awfully concerned about his incessant thumb-sucking. Afraid his habit would cause future dental problems, they tried every remedy they could think of. I remember his thumbs being heavily wrapped in adhesive tape. That didn’t work. Neither did the last desperate measure our parents employed: swabbing his thumbs with the latest advance in thumb-sucking cures. My little brother was unswayed. He stubbornly sucked away, bawling all the while because his mouth was on fire with hot cayenne pepper, the “cure’s” main ingredient. More than sixty years later, Mother still feels guilty about trying that remedy.

We moved back to Florence a year or two later with another brother in tow. In one of those interesting twists of fate, he later became fast friends with Edwin Turner’s son, also an Edwin. Over the years, they shared quite a few adventures of their own. Misadventures, too. But that’s a whole other story—and his to tell. Or not.

*For the hush puppy recipe from Edwin Turner’s Chicken Basket, check outhttp://www.familycookbookproject.com/recipe/3394125/edwin-turners-chicken-basket-hush-puppies.html.

To the astute observer, other signs of autumn’s sure return are all around. Those lime-green spring leaflets that sprouted on trees (wasn’t that just yesterday?) have been growing both larger and darker. Before they put on their showy fall display, they will continue to darken until, in the distance, they’re such a deep green they look almost black.

To the astute observer, other signs of autumn’s sure return are all around. Those lime-green spring leaflets that sprouted on trees (wasn’t that just yesterday?) have been growing both larger and darker. Before they put on their showy fall display, they will continue to darken until, in the distance, they’re such a deep green they look almost black.

To moms and dads everywhere, know that your influence is strong. If you’re the parent of a newly-minted adult, don’t imagine for a minute that you’re not still an almost constant traveler in your son’s or daughter’s mind. Your kids may forget to call, but they are thinking of you. They are talking about you (hopefully in a good way). They are remembering your lessons. You’re still important to them, central to their lives.

To moms and dads everywhere, know that your influence is strong. If you’re the parent of a newly-minted adult, don’t imagine for a minute that you’re not still an almost constant traveler in your son’s or daughter’s mind. Your kids may forget to call, but they are thinking of you. They are talking about you (hopefully in a good way). They are remembering your lessons. You’re still important to them, central to their lives.

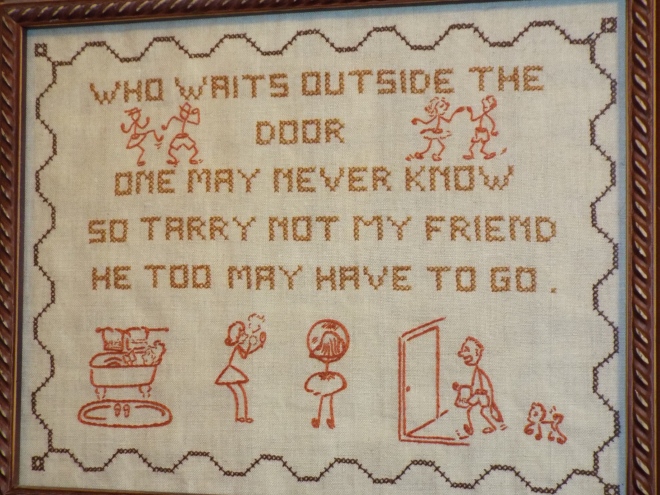

a North Carolina map, birds of America, twin Christmas “Partridge in a Pear Tree” wall hangings, along with humorous or pithy pearls of wisdom. “If Mama ain’t happy, ain’t nobody happy,” and”Nobody sits down until the cook sits down,” and “Use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without” are three memorable ones.

a North Carolina map, birds of America, twin Christmas “Partridge in a Pear Tree” wall hangings, along with humorous or pithy pearls of wisdom. “If Mama ain’t happy, ain’t nobody happy,” and”Nobody sits down until the cook sits down,” and “Use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without” are three memorable ones.

Touch-me-nots are common throughout all of the U. S. with the exception of a few western states. They’re fascinating plants—beautiful, useful, quirky, and irresistible to kids of all ages. Once you’ve popped a few seedpods, you never outgrow the urge when you come upon a patch of these intriguing plants.

Touch-me-nots are common throughout all of the U. S. with the exception of a few western states. They’re fascinating plants—beautiful, useful, quirky, and irresistible to kids of all ages. Once you’ve popped a few seedpods, you never outgrow the urge when you come upon a patch of these intriguing plants.